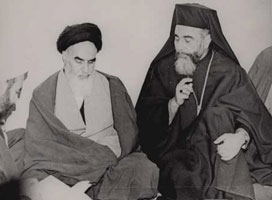

Although there has been talk about seeing the leader of the Islamic Republic, the much hated, much revered Ayatollah Khomeini, I had learned that it was better – with something a portentously important as such a visit – to make the effort and then accept what happened.

…Imam Khomeini was a symbol in the West of the most obdurate atavistic pride and implacable hatred. And even some Westerners with whom I had talked who had met Khomeini commented on his charisma, but in the same breath remarked at the total absence of humour or warmth in his demeanour.

Now I had the opportunity to judge myself.

…Now I was to see in the flesh the personage whose will had dominated Iran, whose policies (although attributed to God) had caused so much disruption in Iran and had drawn so much negativity from the West.

I secured a seat at the front of the hall; Khomeini’s chair, draped with a white sheet, was situated on a stage above us at least fifteen feet from floor level.

…We were there for about forty-five minutes before there were signs that the Imam was about to make his entrance. The signal was clear; several other turbaned 'ulama emerged from the door and indicated to the mullah who was waiting on stage that the chieftain, priest, holy man commander and Imam was on his way. At the appearance of Khomeini in the doorway everyone jumped to his feet and began shouting, "Khomeini!" "Khomeini!" "Khomeini!" in the most vibrant athletic, rejoicing, militant tribute that I had ever witnessed for another human being. Everyone seemed completely taken over by the spontaneous surge of love and adulation, and yet there was the proclaiming with every cell of their heart the absolute confidence that what and who they were honouring was worthy of such honour in the eyes of Allah. Indeed I would say that the explosion of ecstasy and power that greeted the Imam was itself not so much a simple reflex based upon a fixed idea of the Imam; it was rather the natural and exuberant hymn of praise, of celebration that was demanded by the very majesty and overpowering charisma of this man. For once the door opened for him I experienced a hurricane of energy surge through the door, and in his brown robes, his black-turbaned head, his white beard he stirred every molecule in the building and riveted the attention in a way that made everything else disappear. He was a flowing mass of light that penetrated into the consciousness of each person in the hall. He destroyed all images that one tried to hold before one in sizing him up. He was so dominant in his presence that I found myself organized in my sensations by that which took me far beyond my own concepts, my own way of processing experience.

I had expected-no matter what the apparent stature of the man to find myself scrutinizing his face, exploring his motivation, wondering about his real nature. Khomeini's power, grace, and absolute domination destroyed all my modes of evaluation and I was left to simply experience the energy and feeling that radiated from his presence on the stage. A hurricane he was, yet immediately one could see there was a point of absolute stillness inside that hurricane; while fierce and commanding, he was yet serene and receptive. Something was immovable inside him, yet that immovability moved the whole country of Iran. This was no ordinary human being; in fact even of all the so called saints I had met-the Dalai Lama, Buddhist monks, Hindu sages-none possessed quite the electrifying presence of Khomeini. For those who could see (and feel) there could be no question about his integrity, nor about the claim, however muted by people like Yazdi, by his people that he had gone beyond the normal (or abnormal) selfhood of the human being and had taken residence in something absolute. This absoluteness was declared in the air, it was declared in the movement of his body, it was declared in the motion of his hands, it was declared in the fire of his personality, it was declared in the stillness of his consciousness. There was no mystery about why he was so loved by millions of Iranians and Muslims throughout the world and he demonstrated, to this observer at least, the empirical foundation for the notion of higher states of consciousness. Yes, the severity, the humourlessness, the absolutist judgement was apparent; yet given the circumstances within which he was placed, there was the affirmation of appropriateness in his every gesture and aspect. This was the most extraordinary person I had seen.

At first he did not speak; another religious leader addressed the audience, Khomeini sitting in a kind of immaculate silence and perfect equilibrium. He was motionless; he was detached; he was in an ocean of peacefulness; and yet something was in pure motion; something was dynamically involved; something was ready to wage constant war. He dwarfed all those people whom I had met in Iran; he dominated the stage even while the other mullah spoke.

All eyes were on Khomeini, and there was not the slightest trace of egotism, of self-consciousness, even, if I can say it, of inner dialogue or random thinking. His whole being focused relentlessly yet spontaneously on the point of concentration that aesthetically and spiritually fitted into the dramatic scene we were witnessing. Despite the fierce intention, the absolute sense of uncompromising rectitude, there was yet the sense of something perfectly effortless and smooth that dictated the manifest movements of his hands, the sound of his throat clearing, the focus of his attention. Here hundreds of patriots and Muslims had shouted his greatness, had sworn their love, their absolute adulation; yet while receiving all this he remained within himself, he remained unmoved; he remained in the dignity of some imperturbable inner state that was beyond the boundaries of a causation that I was familiar with.

The reader may wince at the extravagance of my description of this man; he must know, however, that despite everything that I had heard, despite the contradictory evidence I had received before (the seeming violence of the rhetoric, the lack of creative playfulness and so on), the actual and immediate impression of what Imam Khomeini was had nothing to do with some sort of idea or concept. The experience was too overpowering for that. Imagine for a moment the pushing of the body of oneself out of one's mother's womb, or the moment when one might awaken to the fact that one was being created inside a foetal body, or the moment when one was conscious of dying, or the moment when one first discovered the power of egos: these experiences have as their basis a primary determinant outside of the frame of reference the individual; what is dominant is the intrinsic nature of the reality which is giving birth to the experience. Such is what happened on the morning of Wednesday, February 9th, 1982 in North Tehran. The subjectivity of the experience seemed to be objectified by something that was at the very basis of my consciousness; I transcended the mode of experience that normally determined what sensations, thoughts, feelings constellated into my awareness of self. Khomeini was that powerful; Khomeini was that strong; Khomeini was that egoless and invincible.

…He was not someone with whom one could discuss the meaning of individual choice, or the sensuous beauty of ballet, but he was yet the most formidable human being on the stage of international politics, and he seemed, at least from my vantage point, to be easily a contemporary of Christ himself; not that Khomeini would ever compare himself with Christ – but he radiated that same uncompromising integrity and one-pointed intention.

…And yet I must go further; Imam Khomeini broke into my heart and my brain with a current of emotion that I can only describe as extreme positivity, what I would prefer to call ‘love’.

By Robin WoodsworthCarlsen, From his book‘The Imam and his Islamic Revolution’